Though the world of wine is filled with drama and intrigue (and a soupçon of scandal from time to time), few tales deliver the drama and mystery surrounding that of Carmenère.

The story reads like a comic-book superhero origin story. Noble grape is thought to be driven to extinction by an evil infestation, but a colony of plantings secretly escapes to take root in a foreign land, living in disguise until their true identity is revealed and they save the world! Or, at least, make a big, positive impact on the world wine industry.

It is thought that the Romans were the first to make wine from Carmenère and it also achieved a measure of popularity in Spain before becoming one of Bordeaux’s most important grape varieties. In Bordeaux, Carmenère was prized for its ability to lend color, complexity and flavorful heft to the region’s red wines. There, it was also called Grand Vidure. Its name was derived from an old French word for crimson thanks to its luscious, deep red color.

Once an important part of red Bordeaux blends, carmenère was thought to have gone extinct after phylloxera.

However, the grape was also a bit finicky, ripening late and prone to mildew and low yields (meaning funky flavors and less wine). When the phylloxera epidemic wiped out France’s vineyards, winegrowers found that their Carmenère vines seemed to be especially susceptible. They also proved to be hard to graft onto resistant rootstock. So most winegrowers decided not to replant it, and the variety was eventually thought to have gone extinct.

Except way across on the other side of the world in Chile, Carmenère vines were thriving in disguise. Chile has been producing wine virtually since the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, making it the oldest wine-producing country in the New World. In later centuries, wealthy Chilean landowners and immigrating French winemakers brought grafts of French grape varieties, including Carmenère, back with them to plant there. Only they apparently didn’t keep such good records and folks just thought these vines were Merlot.

While phylloxera was decimating Europe’s vineyards, Chile was (and remains to this day) unaffected by phylloxera, so its vineyards, including those planted to Carmenère, escaped unharmed. Chile’s luck was likely due to a combination of factors including its geographic isolation between the Andes and the Pacific, with inhospitable deserts to the north and the vast wastes of Tierra del Fuego in the south. The government and winegrowers remain very wary about preventing its appearance as well. Because of Chile’s relatively dry climate, and long, sunny growing season, Carmenère thrived there in ways it could not in Europe’s colder climes.

Around harvest time, carmenère vineyards turn scarlet. Photo source: Concha y Toro.

Then in 1994, a French viticulturalist named Jean-Michel Boursiquot and a winemaker named Claude Valat noticed that some grapes in Chilean vineyards that were called Merlot ripened later than others. They conducted genetic testing that determined these grapes were actually Carmenère! If this were a soap opera, this would be the moment where an identical twin separated at birth shows up in the hospital room of his or her comatose sibling. Drama!

How could people have mistaken Carmenère for Merlot for so long? Well, grapes ripen and taste different depending on where you grow them (have a look at the post on terroir for more on that topic), so folks probably thought that the wines they were making were just the Chilean version of Merlot. That, and Carmenère does bear some flavor similarities to Merlot including luscious berry flavors, some spice, and soft, round tannins that make for good aging and easy drinking.

Initially, that might have been a bit of a blow to the Chilean wine industry, which was thriving on bold Bordeaux-style reds made from Cabernet Sauvignon and what they thought was Merlot. But winemakers in Chile seized on the opportunity to study and perfect Carmenère, and to use it to produce distinctive, unique and, perhaps most importantly, delicious wines that have become a hallmark of the Chilean wine industry. Today, Chile remains home to some 90% of Carmenère plantings in the world, and the grape has become the country’s flagship variety.

Try one of these carmenères for yourself and see what you think.

Want to taste it for yourself? Try these Chilean wines and see what you think!

Casa Lapostolle Cuvée Alexandre: Yes, it’s got some Syrah in it, but just to provide a bit more structure and depth. The vast majority of this blend (85% to be exact) is Carmenère.

Casa Silva Reserva Cuvée Colchagua: Casa Silva is one of Chile’s most distinguished wineries, and this Carmenère is a prime example of the variety with lots of luscious plum flavors.

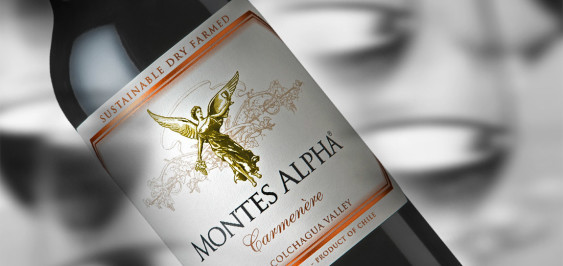

Montes Alpha Carmenère: This is a great example of Chilean Carmenère, with signature notes of spice and pepper, red berry flavors, and hints of both vanilla and chocolate.