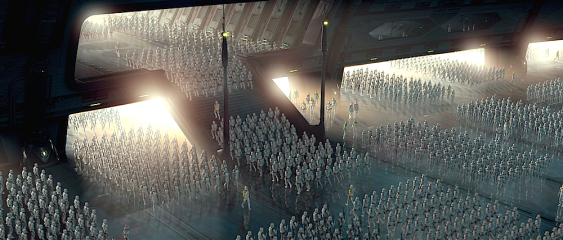

If you’ve been out walking through a vineyard lately (and if you haven’t, make it a goal to visit some this spring when they first start turning green), you might have noticed rows of vines labeled with the variety and a “clone” name. No, the Sith aren’t infiltrating the wine industry. Instead, grape clones are an integral part of winemaking as we know it.

Don’t worry – these clones aren’t a threat to the galaxy!

The term clone was actually coined by a U.S. Department of Agriculture plant physiologist named Herbert J. Webber back in 1903. He derived it from the Greek word klon for new plants cultivated using grafts or cuttings. Thanks to science (both fictional and real), the term has come to mean something having to do with genetic manipulations or replications.

However, the term was originally intended for agricultural usage, and continues to be so when it comes to wine grapes. Winegrowers try to find the right version of a grape variety to plant in particular sites to fit the environment and sync with the profile and overall composition of the specific wine they are trying to make.

Like humans, and pretty much every other living thing, individual grape vines carry naturally occurring mutations – some tiny, some larger – that distinguish them from their fellow vines. So winegrowers look for grape vines with specific traits or characteristics they want to reproduce. Those can include things like resistance to pests, the tendency to ripen early in a colder climate, certain flavor profiles, and even berry and cluster size, Then they take a cutting or bud from the “mother” vine and graft it onto the root of another grape vine.

Why do all these vines look the same? They’re clones!

In other words, this is asexual reproduction or vegetative propagation. You’ll get a gold star, and probably some eye rolls, if you can casually work either term into the conversation at your next dinner party.

The point is to reproduce genetically identical vines. The truth of the matter is that clones often do develop mutations that differentiate them somewhat from their mother vines due to environmental stresses and adaptations. However, they usually remain substantively the same.

This practice became popular back in the 1960s and 1970s, especially as American winemakers looked both to Europe and older vineyards in the U.S. to find clones to cultivate in new vineyards and wine regions.

These days, winegrowers tend to split up their vineyards by plots or parcels on which they plant specific clones that they think will do best on each area of land. For instance, if you were a winemaker in Oregon, you might look into grape clones adapted to the cooler climes of Burgundy rather than those that thrive in California’s warmer appellations to plant on your land.

Sometimes winemakers make parcel-specific, clone-specific wines to try to highlight the qualities of an individual piece of land and the grape variety. Other times, they blend wine made from several clones in order to create a more complex finished product, much as you’d add various spices to a stew to end up with a richer, tastier dish.

Based on the wines you like, you might already have favorite clones without even knowing it.

Some grape varieties have several if not dozens of clones in circulation. Pinot Noir is notable for this (by some estimates, there are over 1,000 clones of it), and you might come across 667, 777 or Pommard. Chardonnay is another grape variety winemakers tend to talk about in terms of clones, and you might see several numbered Dijon clones. Clone 6 is among the most popular Cabernet Sauvignon clone used in California.

So there you have it. Winemakers who deal in clones are not, in fact, raising a sinister army in the pursuit of world domination. Rather, they are trying to maximize both their land and their fruit. All to the benefit of drinkers. So next time you’re walking through the vines, or even just perusing the back label of a bottle, see if you can figure out which clones are being used and why that might be the case.

Have any other questions about clones, or pressing wine matters you want explained? Tweet me @clustercrush!