We owe a lot to the happy accidents of history. The healing power of penicillin, for example. The strength of stainless steel. The…staying power of Viagra. Even fermentation itself, which probably resulted from bread going bad in Mesopotamia (or China, depending on whom you ask), and was turned to the marvelous pursuit of brewing beer.

Numbering among those beneficial happy accidents was the advent of spätlese, or “late harvest,” Rieslings that Germany’s wine industry has become known for over the centuries.

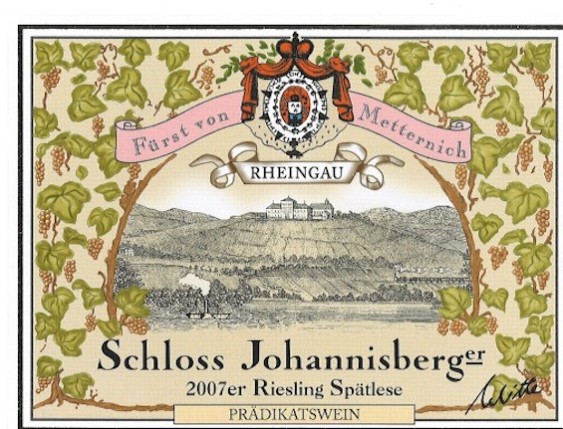

Schloss Johannisberg’s recognizable yellow castle was built in the early 1700s.

Though grapes have been grown at the site of what is now Schloss Johannisberg along the Rhine River since the time of Charlemagne, it has only been planted to Riesling for about 300 years. This former Benedictine cloister came under the control of the Prince-Bishop of Fulda (yes, that’s a real title) in the early 18th century, and he promptly built a massive buttercup-yellow castle on a hill overlooking the vines and the river. Under his aegis, hundreds of thousands of Riesling vines were planted in the area, prompting a German wine boom in the 1720s.

However, the Prince-Bishop himself, and his successors, actually lived in Fulda, about 100 miles away, which would take several days by horse. Well, with wine being such an important part of his holdings, the Prince-Bishop insisted on being sent clusters of grapes each year to determine when the harvest should begin. If he thought the grapes he was sent were ready, he would issue an official authorization to start the harvest that would have to be brought back to Schloss Johannisberg by a herbstkurier, or “autumn courier.”

Everything went like cuckoo-clockwork until 1775. That year, the messenger bringing back the harvest permission was delayed by a week or two. Some conjecture it was because the Prince-Bishop was off on a hunting trip when he should have been issuing his permission. Others believe the messenger was waylaid by robbers and thrown off course.

Whatever the reason, by the time he got to Schloss Johannisberg, the grapes in the vineyard had already become infected with botrytis, a fungus that is now sometimes referred to as “noble rot.” Up until then, however, it was known as a grape-destroying scourge. Basically, it infects the grapes through their skins and sucks the water content out of them, leaving just the sugars behind.

We have a late messenger to thank for one of the world’s most famous wines.

The monks at Johannisberg, not knowing what else to do since the Prince-Bishop expected his wine, tasted that the grapes were quite sweet but seemingly not spoiled by the botrytis. So they decided to harvest them anyway and make wine with what juice was left. Thus was born the world’s first spätlese, or purposely late-harvested wine, with its hallmarks of sweetness, finely balanced acidity and a wide array of ripe fruit flavors. All because some guy was waiting for his boss to sign off on a letter.

Today, when you visit Schloss Johannisberg, you can even see a jaunty sculpture of the tardy messenger, dubbed the Spätelesereiter, bearing his late harvest authorization.

The messenger commemorated in this statue doesn’t seem too upset.

Without his unplanned delay, though, we wouldn’t have some of the world’s finest sweet wines. Think about that the next time someone doesn’t reply to your email or text message right away. You never know what good might come out of it…and in the meantime, you can enjoy a glass of spätlese Riesling!