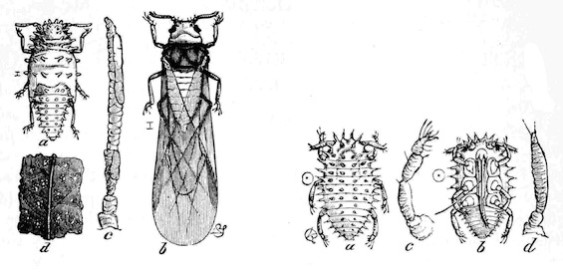

Phylloxera. It sounds like something Toulouse Lautrec might have picked up from a Parisian courtesan back in the day. But this is no social disease. It’s a lousy vine problem. Literally lousy. The phylloxera, also known as the root louse, is a destructive little member of the aphid family that feeds on grapevine roots, causing the plants to wither and eventually die.

Phylloxera is a nasty little beastie.

While we currently live in an age of pesticides and organic practices that can help stop this menace before it infects grapevines, back in the 1800s, winemakers were unfamiliar with this pest…but they would soon come to know it (and fear it) all too well.

You see, in the pantheon of unintended consequences, this was a big one. Back in the 19th century, a little something was taking place called the Industrial Revolution. Folks were building newer, better and (here’s the key) faster everything, including steam engines to power oceangoing ships. Up until that time, phylloxera, which originates in North America, could not survive a long voyage at sea if it was just covertly carried along with grapevines and other crops on the ships transporting them from the United States to Europe.

But with faster engines, the time it took to cross the ocean became just a fraction of what it once was…and those phylloxera were able to hang on just long enough to say “bonjour” to the vineyards of France. (And you wonder why you’re not allowed to transport produce through international customs!)

What became known as the “Great French Wine Blight,” began in the late 1850s and swept through the vineyards of France before bulldozing through the rest of Europe. Sacré bleu! The French, and everyone else, were ill-prepared to handle this sudden, unforgiving epidemic.

It took the French nearly a decade to figure out what exactly the problem was in the first place. And then, well, you know the French. They had to argue about a solution for nearly another decade before getting around to doing something about it. By that time, around the mid-1870s, wine production in Europe was on the brink of collapse.

Only a few parts of the world like Chile and certain regions in Australia are free of phylloxera.

So how did they stop the rot? By going back to the source and creating a hybrid. You see, American grapevine rootstock actually evolved to resist and live with phylloxera. European viticulturalists were able to graft what vines still existed onto this hardier stock, and that’s still what they do to this day. Once the vineyards of Europe were “reconstituted,” wine production went back up and we are all still able to drink Bordeaux and Rioja to this day.

Keep that in mind next time a European winemaker is thumbing his or her nose at American wines. Because essentially, every European wine you drink owes its very existence to American roots. The grafting situation raises an entirely different debate about the quality of intact grapestock versus grafted rootstock, but we’ll leave that for another day.

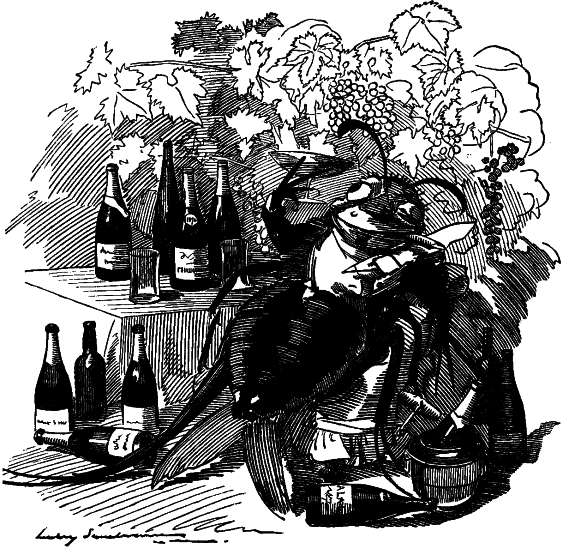

For a typically French take on the phylloxera epidemic, take a look at this satirical cartoon:

Leave it to the French to be crass even when they’re getting their…grapes…handed to them.